Vanilla: a Sweet Flavor with a Sticky History

It would be hard to imagine a modern world without vanilla. Vanilla is one of the world’s most popular scents and flavors. It has been used for centuries, and the demand for vanilla far exceeds natural production. In fact, it is estimated that roughly 18,000 metric tons of vanilla flavor is produced annually, much of which (about 85%) is synthesized from the petrochemical precursor guaiacol. The United States is the world’s largest importer of vanilla beans, accounting for $348 million worth of beans imported in 2022, which equals just over a third of the world’s sales of vanilla beans.

Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia) is an orchid native to Mexico, central America, Colombia, and Brazil. According to Lubinski et al (2008) vanilla was used in pre-Columbian Maya of southeastern Mexico/Central America to spice up drinks. (Interestingly, their research also assumed that these former cultivars are not what is used in commercial production today, too). Despite its importance around the world, we still do not know the main pollinator (or pollinators) of vanilla. The stingless bee Melipona beecheii is believed to be the main native pollinator, but little evidence exists to corroborate this claim. Outside of its native range, male orchid bees (Euglossa and Exeretes) have been observed visiting vanilla as well ants and hummingbirds.

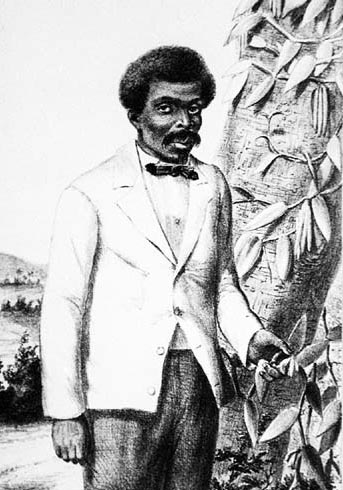

In the 1820s, French colonists brought vanilla to Réunion, a small island east of Madagascar. Despite their efforts, the vines failed to produce fruits as no local insects would pollinate them. Enter Edmond Albius, an enslaved 12-year-old, who came up with a genius hand-pollination method using a simple stick and thumb gesture. It was 1841, and his revolutionary breakthrough turned vanilla production into a booming industry. Not only was his technique important for vanilla, but it also could be transferred to other plant species as well. His methods are still used today many, many years later.

Edmond remained a slave until 1848 when France re-abolished slavery. Before he was released, he spent several years traveling and teaching other slaves how to hand pollinate orchids using le geste d’Edmond, Edmond’s gesture. Following release, he struggled to find work. He worked as a laborer and as a kitchen boy. One night, a theft occurred at the estate he was working at, and Edmond was blamed and sentenced with five years in prison. His former enslaver, F. Bellier-Beaumont and others appealed for his release and were eventually successful thanks to his contributions to the community. He later married but died years later in poverty. His memory and mark on modern botany live on, though.

Today, vanilla is grown around the world. While Madagascar vanilla (V. planifolia) is the most popular vanilla in production, growers also produce Tahitian vanilla (V. × tahitensis) and V. pompona. Since vanilla is still hand-pollinated, it is quite expensive and production cannot keep up with demand. In fact, one article I read stated: “Cured vanilla beans contain only 2% of extractable vanilla flavor, meaning prices for pure vanilla reached an eye-popping $11,000 per kg. The industry is closely watching this year’s harvest, hoping to see vanilla costs eventually return to pre-2012 levels of about $25 per kg for beans or $1,250 for vanilla.” Wow! As a note, the synthetic vanillin made from the petrochemical precursor guaiacol is about $10/20 per kg to produce which is why it accounts for most of what we consume. Unfortunately, while guiacol vanillin production is cheap, it’s not sustainable and greener alternatives are being explored.

Several years ago, I was given a book, “Make the Bread and Buy the Butter” which got me to experiment making different things at home. One of those experiments was homemade vanilla extract due to the high price tag at the store and ease of making it at home. Since then, we have made different variations of extract flavors and provided them as gifts. Two important notes: the beans need to be fresh and oily, and you have to wait at least 2-3 months for the extract to mature.

To make vanilla extract, all you need is an amber glass bottle, vanilla beans (12 per 16 ounces), and some 70 proof alcohol. I prefer to cut the ends off my beans and split them down the middle before placing them in alcohol. A cheap white rum will do, but we also like to use golden rum for some as it imparts a bolder flavor for baking. Golden rum vanilla is more of a unique extract, as well. Once the beans have been added to the bottle, give it a good shake and place it in a dark cabinet (light can degrade the extract). Shake it every couple of weeks, strain out the seeds and pods, and add them to extract bottles. Some people reuse their old pods for a second batch. Apparently, you can also dry them out and grind them up for vanilla powder. I might try making powder this year.

This year, I had extra beans, so I made my first batch of vanilla sugar. It’s also simple! For every 1/2 cup of sugar, add the scrapings from one bean, seal in a container, shake, and wait.