Eastern Coyotes

A tale I often hear is how Maryland and other state wildlife agencies secretly introduced coyotes into their states. Sometimes, the release was done in conjunction with insurance agencies. Sometimes, it was done just because. People will repeat stories of coyotes running around with “State Farm” ear-tags and the secrecy of the project to reduce burgeoning deer population numbers. These stories often include an unnamed cousin/friend/confidant who saw the process firsthand, but no proof outside of that oral story exists.

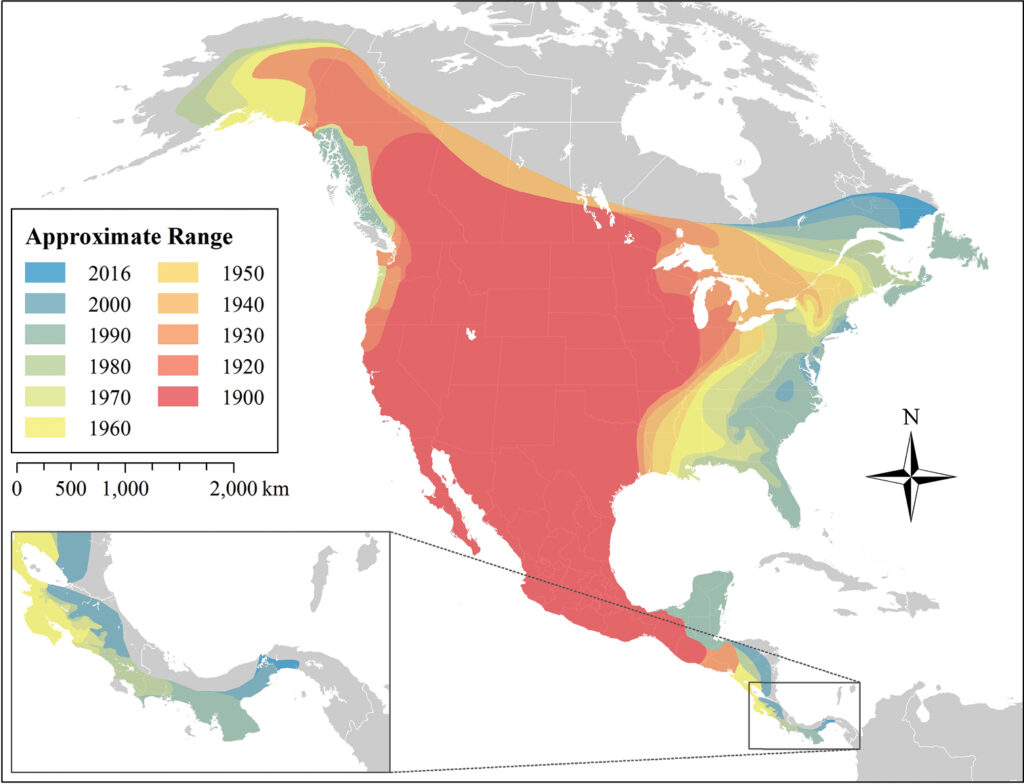

The truth is less noteworthy: eastern coyotes migrated east over the course of 100 years in a slow, well-documented progression with Maryland and Delaware being the last two eastern states to formally confirm coyote presence. Maryland’s official reports first came in through Cecil, Frederick, and Washington counties.

Range expansion figure from: Hody JW, Kays R (2018) Mapping the expansion of coyotes (Canis latrans) across North and Central America. ZooKeys 759: 81-97. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.759.15149

Multiple colonizations have occurred in our area. Some of the eastern coyotes came in through a southern route while others took a more northern route. The latter group have some genetic admixtures with Great Lakes wolves. This hybridization has caused media-hyped names like coywolves and coydogs to describe the eastern coyotes we have in Maryland. The eastern coyote definitely has some traits that make them different from their western cousins, but the two populations haven’t officially been split, yet. What we have in Maryland are also majorly comprised of coyote genes, so we’ll call them eastern coyotes in this blog. [As an aside, the American Society of Mammalogists accepts Canis latrans as the only extant coyote species in the United States though some have argued to split this species.] The concept of a species isn’t as black and white as we once thought it was, especially with new genetic technologies revealing more about genomes than we ever imagined. In fact, wild carnivores often hybridize with conspecifics (closely related species). Furthermore, some of us even carry trace amounts of Neanderthal genes from our ancestors, and we don’t lump them out into a Hu-man-der-thal group. Humans like to place nature into neat categories, but biology is always on a spectrum.

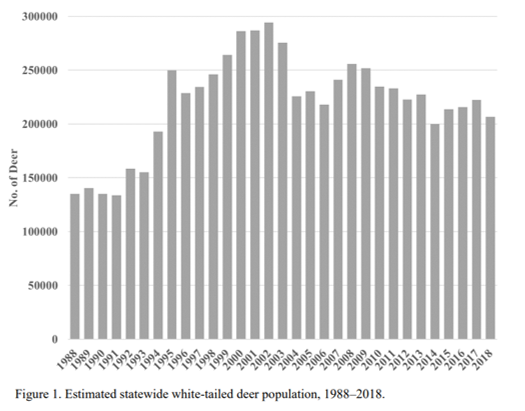

One of the reasons people believe coyotes were intentionally released was to control deer populations. This is also a myth for several reasons. First, in places like Maryland, deer populations were not a problem in the 1970s when coyotes first entered the state. Until the 1980s, Maryland had a strict permit system for white-tailed deer harvest, and cultural carrying capacity (aka how many of an animal species the human population can tolerate) wasn’t hit until the mid-1980s in Maryland. You can read about Maryland’s historical deer numbers in the 2020-2034 Deer Management Plan. Next door in Virginia, the state managers were actively trying to increase the deer herd size through the early 1980s until their management objectives changed. Essentially, there was no need to engage in a secretive release of non-native mesocarnivores for a problem that didn’t exist.

Graph of 1988- 2018 deer population levels from the 2020-2034 Deer Management Plan.

In addition, coyotes are not known to be effective at controlling deer populations in most of eastern North America. Anecdotally, if you look at the graph above, you can see the deer population in Maryland almost doubled following colonization by coyotes. Coyotes now can be found in every county in Maryland and even in Baltimore City. A Penn State study found that while coyotes do kill some deer, they do not impact population levels. On a larger scale, researchers have examined deer population numbers throughout 6 eastern states and 384 counties and found that coyotes were not impacting deer population numbers. A rebuttal to that study, however, did show that there are some localized impacts of eastern coyotes on deer. So, it is important to acknowledge that this issue is nuanced depending on factors like location and other impacts to deer herds like disease.

Of course, eastern coyotes are consuming deer, usually in the form of fawns or scavenging road-killed deer. Many eastern coyote diet studies have assessed scat samples which can show items consumed and quantities but do not shed light on how those items were obtained (aka a scavenged deer vs one that was hunted and killed). A small undergraduate study in western Maryland found that out of 17 coyote scats analyzed, small mammals and birds made up most of their diet followed by deer. Surprisingly, almost 20% of the scat samples also contained invertebrates. As with most mammals, the diet of eastern coyotes shifts with the seasons and food availability.

In Maryland, eastern coyotes typically begin their breeding season towards the end of January. During this time, male coyotes are hopped up on testosterone, making them bolder and a little more aggressive. For most people, this is not an issue. However, if you have small dogs or cats that go outdoors, coyotes have a higher propensity to attack during this time. Be vigilant. Don’t let pets outside unattended from dusk to dawn. If you see a coyote hanging around, then be extra cautious when letting pets outside. Clap your hands and make loud noises in an attempt to scare the coyote away.

In my many years as a local naturalist, I have not seen a live coyote in Maryland. I have heard them. I have come across tons of sign (scat and tracks), but I have never seen one of these secretive creatures here except dead on the road. I think one of my most memorable coyote sign stories was finding a pile of coyote scat on top of a log that contained a rodent nest. It was clear the coyote was marking this location for a reason. Somewhere in the digital world, I have a photo of that find, but alas, you will have to settle for another photo depicting older coyote scat containing parts of an eastern gray squirrel. (Yes, I dissected this scat and the orange line towards the top was a squirrel incisor).

Like it or not, eastern coyotes are here to stay in the eastern United States. Some studies have shown that coyotes will respond to control efforts by compensatory breeding or immigration (aka having more babies or moving into new territories). Like the deer population impacts, these conclusions are nuanced and are not always the case. One study looking at lethal and nonlethal management options for coyotes did suggest removal of problematic individuals from a population might be an effective control as well as learning to live with coyotes (and other wild neighbors). In Maryland, eastern coyotes are classified as furbearers and can legally be hunted with a license during set seasons. USDA Wildlife Services also provides free advice for folks dealing with nuisance wildlife issues via their wildlife hotline: (877) 463-6497.

Ultimately, coexistence with eastern coyotes requires a balanced approach that combines responsible management with public education on how to minimize conflicts. Understanding their behavior and ecological role can help foster a harmonious relationship between humans and these adaptable critters.