#Arachtober: Secrets of the Silk

Spider silk has always been a supernatural material. It’s strong, stretchy, and lightweight. University of Leicester’s Physics students have even determined that it could stop a train (like in Spiderman) if the silk came from Darwin’s bark spider (Caerostris darwini), an orbweaver with strong silk. But, what exactly is spider silk made of? And why do they need it to be so strong? Let’s explore the secrets of the silk.

Spider silk is pretty elaborate and made from a combination of proteins and other ingredients mixed together in the glands in the butt (abdomen) of the spider. Spider species such as our local Araneus diadematus can have as many as seven different types of silk, all slightly different based on their function for defense, feeding, and/or reproduction. As the silk proteins are secreted, they travel down narrowing ducts where the pH slowly decreases, causing silk fibers to form (explanation here). (As an aside, I joke with kids that spiders are butt chemists, and this produces a lot of giggles). The different glands and silk mixtures will make the different types of silk. Silk isn’t inherently sticky, either, and glue has to be added to certain strands to assist with prey capture. Spider silk glue is also fascinating- it is a sticky polymer that stretches and doesn’t change when it gets wet. Because of this, researchers are looking into how to apply these polymers for human applications- like bandages that stay on underwater.

Smithsonian Magazine has assembled a list of fourteen different ways that spiders use their silk. One of the neatest examples, at least to me, is how the aquatic diving bell spider (Argyroneta aquatica) spins a silken bubble which it fills with oxygen and uses to live underwater. The bubble serves almost like an oxygen tank and requires occasional trips to the surface to refill. This species of spider can be found in Europe and parts of Asia.

Salticids (jumping spiders) typically don’t build webs, but they do use silk to create protective cocoons for molting and also to assist with silk draglines (which I affectionately call ‘butt brakes’). The draglines have long thought be to used just for a safety line as jumping spiders jump off of tall surfaces and need to stop along the way. Chen et al. (2013) found that it also helped to stabilize the spiders in mid-air.

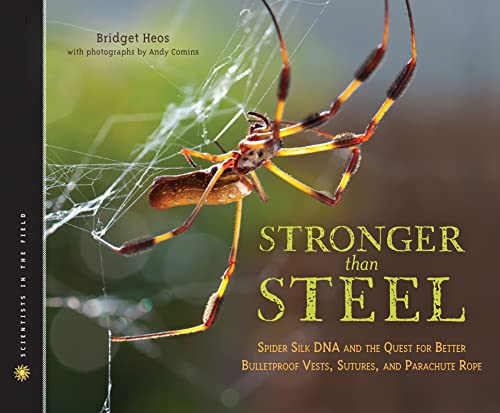

Not only is spider silk amazing for spiders, humans have long been interested in its applications. One day, spider silk might be able to mend bones, repair damaged nerves, dress wounds (sidenote: ancient Greeks and Romans used this years ago!), and making bulletproof vests and skin. One of the largest issues is producing spider silk in quantities needed for these materials. Scientists are actually turning towards using genetically engineered goats to produce spider silk in their milk. A cool book that explores this concept for students is: Stronger Than Steel: Spider Silk DNA and the Quest for Better Bulletproof Vests, Sutures, and Parachute Rope (Scientists in the Field Series) by Bridget Heos.

Other great books for younger kids include Spinning Spiders (Let’s-Read-and-Find-Out Science 2) by Melvin Berger and Next Time You See a Spider Web by Emily Morgan. (Note- I don’t get any kickbacks for recommending books; I just like to educate). 🙂