Of Poop and Parasites: Rafflesia

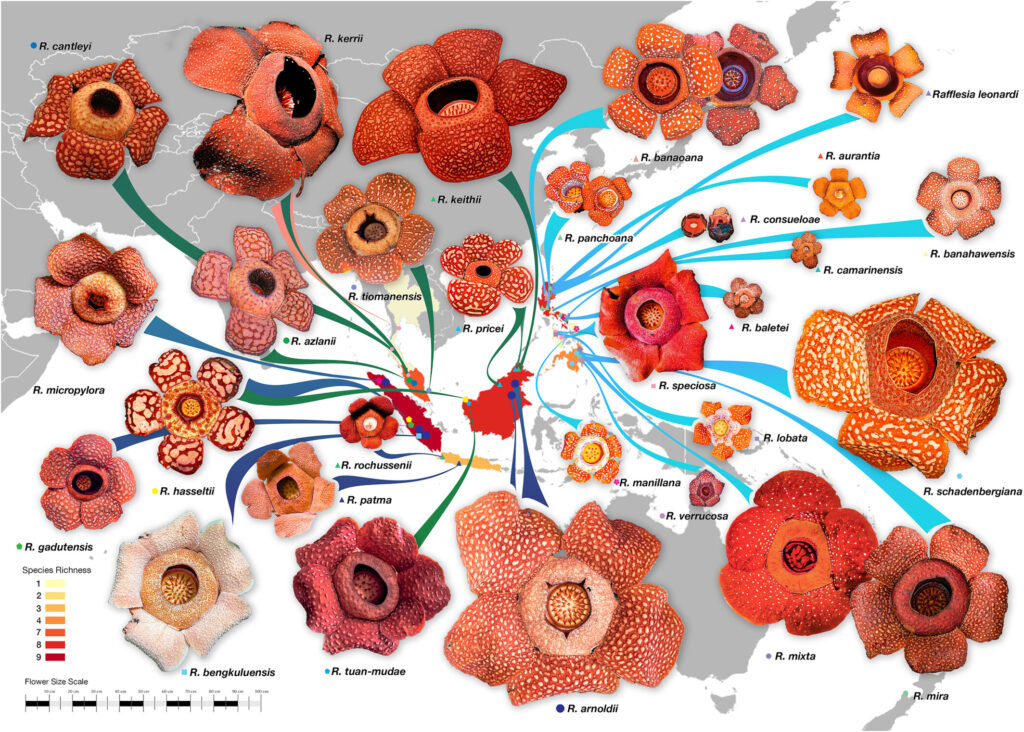

In the rainforests of southeast Asia, the largest flower species in the world can be found along the forest floor or climbing up vines: Rafflesia. Rafflesia is a genus of around 41 species of parasitic plants, almost all of which are threatened or endangered. The largest flower ever recorded was just over 4 feet in diameter and weighed close to 20 lbs!

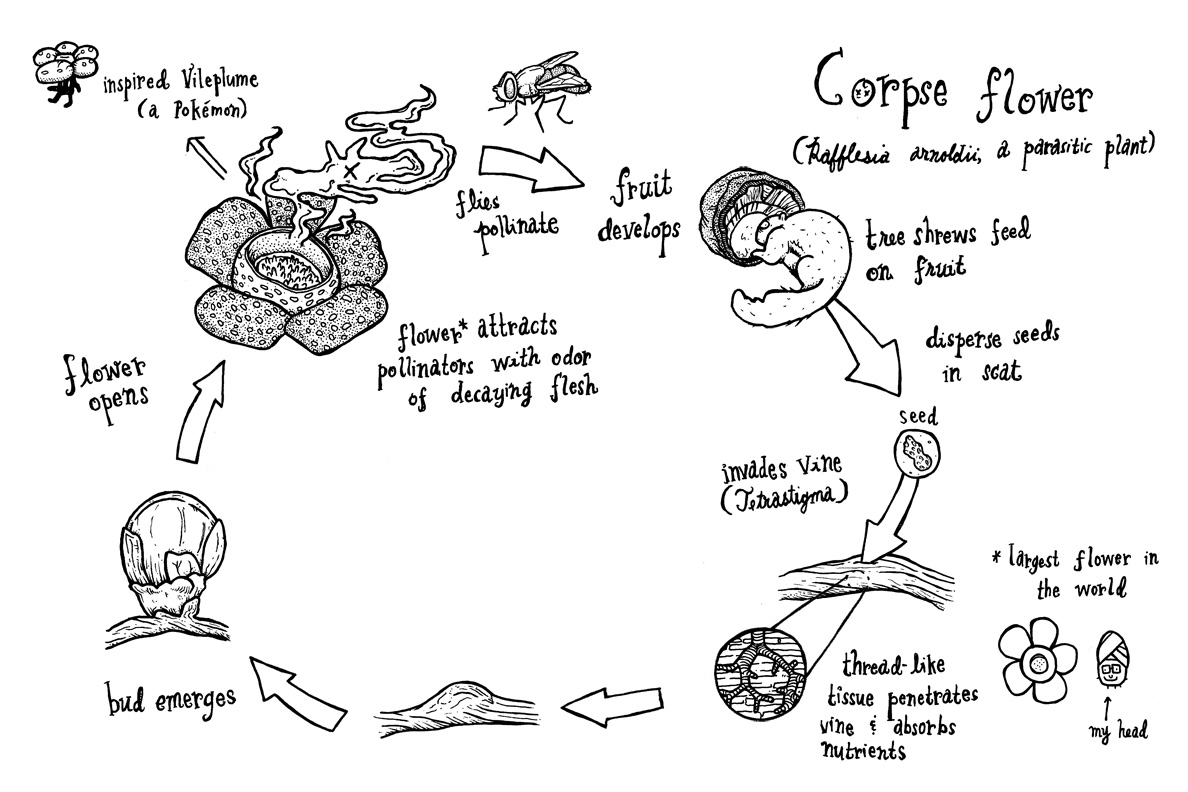

Rafflesia parasitize the Tetrastigma vines which are found in the grape family (Vitaceae). Dispersal of the fruits is not well understood. Some are moved by ants, some are moved by pigs, and some are moved by tree shrews and plantain squirrels. One account mentions that the tree shrews and squirrels will poop digested Rafflesia material on the host vines, allowing the partially digested seeds to sprout and take root. [This is similar to other parasites like mistletoe]. Another account mentions the fatty tissues on the seeds (elaiosomes) attract ants which take them to their nest, preferably (for the plant) by the roots of its host.

Regardless, once the Rafflesia comes in contact with its hosts, it gets to work. The parasite will attach to its host and penetrate its cells to extract nutrients. Rafflesia has no true roots, rather it uses root-like appendages known as haustoria to sap nutrients away. Interestingly enough, researchers have found that it not only takes water and nutrients but also genes from its host in the form of horizontal gene transfer! Once enough nutrients are acquired, a bud will form. It can take some species YEARS to get from bud formation to flowering. The buds start out as dark colored balls on the vine which eventually develop into reddish cabbage-shaped balls. Once it officially blooms, the flower lasts anywhere from 3-8 days.

The flowers are large, fleshy, and stinky. They are nicknamed ‘corpse flowers’ due to smelling like rotting flesh. The large flowers are also reddish in appearance with cream or white spots on the petals. The look and smell are nice and attractive for their main pollinator: blowflies. Of course, it takes energy to smell so bad, so the scents peak at certain times of the day to maximize visitation. In addition, at least one species, Rafflesia tuan-mudae, is endothermic, cranking up its internal temperature a few degrees to mimic a rotting corpse.

While several species can be found throughout Malaysia, Gunung Gading National Park in Sarawak is a well-known spot to see Rafflesia tuan-mudae. This species is considered to be critically endangered. The Park was established in 1994 specifically for Rafflesia conservation, and they will regularly post on their Facebook page when plants are close to blooming. When we visited, we knew there was a caged bud a few weeks away from opening. However, we weren’t expecting to see one in bloom right off the trail. To say I was stoked is an understatement.

As a child, I was always fascinated with nature and learning about exotic animals and plants. I did a project on parasitic plants in high school and first learned of Rafflesia then. I would daydream about seeing one and never expected I could get the opportunity to do so.

As much as I wanted to touch the flower, I knew it was harmful and likely not allowed. I did get some good pictures of its internal structure, though. What you see in the center of the window are called processes on the central disk. The actual flowering parts such as the stamen and pistil are actually hidden. So, it’s not easy to distinguish male vs female flowers without probing in the plant.

Rafflesia is a cultural symbol. It is one of three national flowers for Indonesia. Some groups also see it as a symbol of fertility. Others view it as a delicacy. In Borneo, Rafflesia ecotourism is popular. Unfortunately, habitat loss and degradation, climate change, and exploitation all threaten these enigmatic plants. It is believed there are still several undescribed species that may be lost before they are known, too. At present, no plants have been able to be cultivated in captivity, but some researchers in the Philippines are coming close! I hope their research prevails, and we can save this captivating group of creepy plants.